Joan Mulholland was watching television one day when something flashed across the screen that gave her chills.

Joan Mulholland was watching television one day when something flashed across the screen that gave her chills.Unarmed young men and women blocked rows of tanks. Giddy demonstrators placed flowers in soldier's bayonets. Protesters sang "We Shall Overcome" -- with an Arabic accent.

The images hurled the retired schoolteacher back to another moment in spring when she was a teenager risking her life for change. In May 1961, Mulholland joined the "Freedom Rides." She was part of an interracial group of college students who were attacked by mobs and imprisoned simply because they decided to ride passenger buses together through the Deep South.

"So much of what has happened in Egypt is like déjà vu," says Mulholland, who appears on PBS Monday at 9 p.m. in a mesmerizing documentary called "Freedom Riders."

"The pictures that have been in the news have been almost interchangeable with the civil rights movement here years ago," she says about the Egyptian protests that toppled a dictator. "I've seen so many visual parallels that I'm starting to save pictures in a scrapbook."

The Freedom Riders were called communists and outside agitators. As they commemorate the 50th anniversary of their rides this month, another group of people in the Middle East is calling them something else -- inspiration.

Several leaders in the protests sweeping the Middle East say they are using the same nonviolent playbook Freedom Riders and other civil rights activists used years ago to resist oppression.

Dalia Ziada, North Africa director of the American Islamic Congress, a group that promotes interfaith tolerance, says some Egyptian protesters took heart from the disciplined nonviolent resistance activists once displayed during civil rights campaigns like the Freedom Rides.

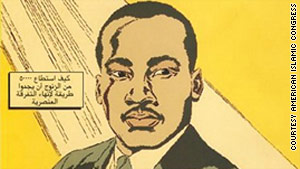

A comic book on the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. is spreading across the Mideast.

"It was inspirational," she says. "I realized that no matter how long it takes, nonviolent tactics lead to success in the end. This made me and all my colleagues here in Egypt stand strong in the face of police brutality during revolution time.''

Reading MLK in Arabic

At first glance, there seems to be little connection between Freedom Riders and the "Arab Spring," a wave of civil uprisings sweeping the Middle East. The series of protests are being driven by people from various ideologies that have nothing to do with nonviolence.

Yet there are signs that the seeds of nonviolent resistance that Freedom Riders and other civil rights activists planted years ago in America are being scattered throughout the Arab Spring.

And some are now starting to sprout:

A 50-year-old comic book explaining the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s philosophy of nonviolent resistance has been adopted by Egyptian protesters and distributed throughout the Mideast.

The comic book, republished in Farsi and Arabic by the American Islamic Congress, has attracted so much attention that Georgia Rep. John Lewis, a Freedom Rider leader, has marveled publicly over its impact.

Ethan Zuckerman, founder of Global Voices, an international group of journalists that hosts conferences for Arab bloggers, says many Arab protesters have deliberately shunned violence.

"The protests began, at the very least, as explicitly nonviolent events," he says. "In many of the marches, not just in Tunisia and Egypt, but in Bahrain and Syria, protesters have chanted 'Peaceful, peaceful', making it clear that any violence from the military was an overreaction."

The New York Times ran a recent profile on Gene Sharp, an elderly American author of books like "The Politics of Nonviolent Action" who has discovered that his books are popular reference guides for protesters in Egypt and Tunisia.

One of the Freedom Rider leaders, Bernard Lafayette Jr., has already established three nonviolent training centers in Palestinian territories.

He says many Arabs can relate on a visceral level to the brutality Freedom Riders and other civil rights activists faced.

Freedom Rider Joan Mulholland after being arrested at age 19 for riding with black passengers on an interstate bus.

"There's a direct connection," Lafayette says. "They've gotten a chance to see the film footage and a chance to read the history of the movement in the U.S. and the success we've experienced."

One of those Palestinian leaders inspired by Lafayette is Sami Awad, executive director of the Holy Land Trust, a Palestinian nonprofit group that works to develop nonviolent approaches to ending what it calls the Israeli occupation.

Awad says he was inspired by the civil rights movement as a teenager. His uncle, a nonviolent activist, constantly invoked the movement's leaders and tactics.

"I even remember reading children's comic books, with stories of MLK, even in Arabic, that my uncle would smuggle into Palestine with other materials on nonviolence because they were illegal under Israeli occupation," he says.

Awad says the contemporary footage of Arab protesters confronting Arab dictators reminds him of the old civil rights films he has watched.

"Seeing the people of Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen and Syria break the barrier of fear and be willing to stand in front of armies and tanks with open arms in nonviolence brings back immediate memories of what happened in the South during the '60s," he says.

'We were past fear'

Some of the Freedom Riders who broke through their own barriers of fear 50 years ago still sound amazed at their actions, the PBS documentary reveals.

Most didn't have any support except for one another. Their parents didn't approve. Nor did leading civil rights leaders. Federal and state officials warned them they couldn't protect them.

They stepped on the bus anyway for perhaps the same reason some Arab youths joined the crowds in their country -- they didn't want to miss history.

"It was like a wave or a wind that you didn't know where it was coming from or where it was going, but you knew you were supposed to be there," said Pauline Knight-Ofosu, a Freedom Rider, in the PBS documentary directed by award-winning filmmaker Stanley Nelson.

Courage, though, can evaporate once someone gets hit with a club upside the head. But that didn't happen to most of the estimated 400 students who eventually joined the Freedom Rides, the documentary says.

Though mobs burned a bus and beat riders, and state officials sentenced some to state prison, the Freedom Riders kept coming.

Joan Mulholland says there's a link between her Freedom Rider activism and Arab protests.

Some admitted, though, that there were moments when they doubted their decision.

Ivor "Jerry" Moore recalled walking into an Alabama bus station and locking eyes with a reporter as they both realized a mob was coming for Moore.

"Our eyes met and when he looked away, my very guts shook," Moore said in the film. "He must have thought we were doomed."

The mob attacked Moore and might have killed him if a photographer hadn't distracted them by taking their picture.

Mulholland, who traveled from her hometown in Arlington, Virginia, for the Freedom Rides, said their determination eventually eclipsed their fear.

"We were past fear. If we were going to die, we were going to die, but we can't stop," she said in the documentary.

What happened to the Freedom Riders afterward?

Their rides, first organized by James Farmer and a civil rights group called CORE, made international headlines. They attracted the support of King and embarrassed the Kennedy administration into acting.

At one point in the documentary, the camera captures then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy at a press conference where he defensively said that life for blacks was getting better.

There is no reason in "the foreseeable future that a Negro couldn't be president of the United States," he said.

Three months after Kennedy made that statement, while hundreds of Freedom Riders were in jail, Barack Obama was born.

So much of what has happened in Egypt is like deja vu.

--Joan Mulholland, Freedom Rider

--Joan Mulholland, Freedom Rider

RELATED TOPICS

The Freedom Riders eventually forced the federal government to issue a sweeping desegregation order for bus and rail stations. Five months after they began, they were victorious.

"It was the first unambiguous victory for the civil rights movement," says Raymond Arsenault, author of the book "Freedom Riders," on which the PBS series is based.

"They showed you could go into Alabama and Mississippi and win. They were willing to die to make a point."

Arsenault says he sees the same spirit in the Egyptian protesters.

"All they had was their courage and commitment. They didn't have weapons, huge amounts of funding or international support. It was the same with the Freedom Riders."

He says many Freedom Riders went on to become "shock troops" for other civil rights campaigns.

A half-century later, the wave they joined is still surging, he says.

"They had no reason to believe they could pull it off," Arsenault says. "Their elders in the movement were telling them that they were crazy and were going to set the movement back. But they weren't waiting for the courts or their leaders. They wanted freedom now, not freedom later."

No comments:

Post a Comment