Greensboro, North Carolina The midday buzz of Greensboro business chatter fills the Liberty Oak Restaurant & Bar, where black and white diners make deals over fine white tablecloths.

Greensboro, North Carolina The midday buzz of Greensboro business chatter fills the Liberty Oak Restaurant & Bar, where black and white diners make deals over fine white tablecloths.Around the corner, on Greene Street, a young couple -- one black, one white -- walks hand-in-hand in front of the Carolina Theatre, where black people were once allowed to sit only in the balcony. And across the street at City Hall, African Americans have won unprecedented positions of political power in Greensboro in the past four years, including mayor and city manager.

The 2010 census showed the South is becoming more diverse, and that descendents of African-Americans who migrated North decades ago are now heading South. For the first time, Greensboro's minorities outnumber white residents, 51.6% to 48.4%, census data showed. The city's African American population increased by nearly 31% in the past decade.

It's a subtle shift, but even after so much progress, it matters. Residents said it could change the political and economic power structure that has long been in place in cities like Greensboro.

"That was really striking," University of North Carolina at Greensboro economist Andrew Brod said, explaining that African-Americans with roots in the region returned to be close to family.

David Richmond (from left), Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan) and Joseph McNeil after their 1960 protest.

Decades ago, this city was a catalyst in the civil rights movement. Downtown, there's a civil rights museum around the famous Woolworth's lunch counter where four young African-American men staged their historicsit-in protest a half-century ago. It's all miles away from the infamous street where a confrontation between the Ku Klux Klan and communists turned deadly in 1979.

Despite a changing population and opportunities to learn from its history, racial tensions haven't disappeared in Greensboro, longtime residents say. On the street, residents of Greensboro acknowledge a geographic racial divide between the minority-heavy east side and the mostly white west side.

"There's bitterness out there still," said Jim Schlosser, 68, a Greensboro native and retired civil rights reporter for the hometown News & Record newspaper. "It's subtly changing, but the east side is still black, and there's just not much economic development." The city has been challenged by disappearing textile mills. The once locally dominant industry has been waning for decades, as jobs go elsewhere.

Behind the polite, Southern veneer of this city of nearly 270,000, voters' angry voices rise up in the City Council chamber, linking modern political and budgetary issues to racial divides.

The site of Greensboro's historic 1960 sit-in protest is preserved at the International Civil Rights Center & Museum.

"You would think racial issues would be the last thing to cause tension because people would have learned from racial inequality through the years," said Sharon Hightower, local NAACP board treasurer and a Greensboro resident since 1986. "It's like we're going backwards."

Legacy of protest

Inside Greensboro's International Civil Rights Center & Museum, there's a line of blue and red stools beside a Woolworth's counter. It's the same spot where student protesters risked their lives just by sitting at the whites-only lunch counter.

"They didn't know if they were going to walk out of here or be carried out of here," said museum co-founder Melvin "Skip" Alston.

Race and diversity will be the subjects of classes and community discussions at the museum, said Alston, who also serves on the county Board of Commissioners.

"We'll come to find out we have more in common than we are unlike each other," he said. But the city still has "a long way to go" to achieve racial harmony, he said.

It's like we're going backwards.

--Sharon Hightower, Greensboro NAACP

--Sharon Hightower, Greensboro NAACP

It's still coming to terms with its history of protest. The sit-ins ushered in a string of Greensboro demonstrations, including some that turned violent, such as a three-day protest by African-American students in 1969.

Demonstrators clashed with police after a dispute at an African-American high school, according to Civil Rights Greensboro, a preservation project led by North Carolina's state library and universities. Escalating violence prompted the mayor to declare a state of emergency and the governor to deploy National Guard troops at predominately black North Carolina Agricultural & Technical University.

When it was all over, a college sophomore unaffiliated with the protest had been shot to death, apparently by mistake. Ten years later in 1979, communist demonstrators at a low-income housing project were attacked by armed members of the Nazi Party and the Ku Klux Klan. The event became known as the Greensboro Massacre.

Five demonstrators were shot dead. Survivors accused police of failing to offer proper protection. No one was convicted in the killings, although the attack was captured on TV news film.

"It was a very traumatic episode in the life of this city," said the Rev. Nelson Johnson, who survived the attack.

So traumatic, Johnson said, that the city has been trying to forget about it ever since. In 2005, an independent "truth and reconciliation commission" held public hearings to learn about the attack and to help the community heal. Based on a commission recommendation, the City Council voted in 2009 to officially express regret.

Mary Rakestraw, who voted against the statement of regret along with three other council members, said some people simply want to keep the issue "festering."

"Let's move forward," Rakestraw said. "I think that's what people want to do, and that's from both sides. That's from blacks and whites."

Johnson doesn't believe it. Thirty years after the attack, Johnson said the city is "almost beyond denial" regarding race relations.

"We now need to figure out what to do," he said, as race still divides the city.

East and west

In the mostly black east side neighborhoods of Greensboro, there are no major shopping malls and few major-name grocery stores. It's a fact not lost on many residents.

"There are things missing in east Greensboro that need to be going on here," the NAACP's Hightower said from her eastside home. "We have to travel to the west side to go to the better stores, the better shops."

"There are people who want to make it a racial issue when it's not," says City Council member Mary Rakestraw.

Lately, the intersection of race and geography has triggered voter anger pointed at the City Council.

The city planned to reopen a landfill on the northeast side of the city. The move would save millions of dollars spent every year to export garbage out of town. Opponents accuse council members of selling out a neighborhood of mostly black residents.

Some also say the council's approval of newly drawn boundaries for City Council districts also carried racial undertones.

Reassigning voters to other districts could weaken political influence in less affluent neighborhoods, opponents said. Residents would be denied opportunities to pass legislation that might attract more businesses and jobs, they said.

Lawmakers voted 7-2 on a compromise plan to reassign 5,522 voters to three different districts. The plan now goes to the U.S. Department of Justice for final approval.

"There are people who want to make it a racial issue when it's not," Rakestraw said. "There are certain people that are going to look at every issue with an eye that you're doing it only because of racial impact."

In the past, Hightower said, the council "made an effort to be more considerate of both sides of town."

"They still fought, don't get me wrong, but they knew how to do it and how to come to a consensus that was for the greater good," she said. "And we don't have that anymore."

These are the kinds of fights that can make or break a community's mood, reputation -- and growth.

"Greensboro has continued to portray itself as moderate and progressive," said Duke University professor William Chafe, author of "Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Struggle for Freedom." "But the realities of it are that it has not changed that much because the underlying issues of seriously listening to black concerns have not really infiltrated the political process."

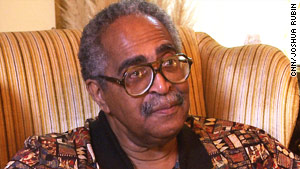

Now 69, 1960 sit-in protester Franklin McCain says Charlotte racial relations have progressed faster than Greensboro's.

Franklin McCain -- one of the four Woolworth's protesters -- is now 69 and retired from a career in chemical engineering and sales. McCain said racial relations have progressed faster in nearby Charlotte, thanks to savvy business leaders who made tough decisions aimed at opening opportunities and improving the city's image.

The results: Charlotte's population exploded during the last decade, got more diverse and got a big win when it landed the 2012 Democratic National Convention.

"There is not the openness between the races in Greensboro -- there's more of an air of mistrust there," McCain said. "Greensboro is probably where Charlotte was 25 years ago."

Back in Greensboro, unemployment rates in 2000 and 2010 have hovered about 4.5 percentage points higher for blacks than for whites, according to Census Bureau data. Median annual household income for white Greensboro residents has increased $5,300 from 2000 to 2009, according to Census data. For African-Americans, that number increased by only $11.

Breaking through

Residents sense a divide in the city, but according to a Brookings Institution analysis, the Greensboro-High Point area is the middle of the pack in terms of racial segregation in the 100 largest cities.

Segregation has eased somewhat in the past decade as more African-Americans move into white neighborhoods, said Afrique Kilimanjaro, editor of The Carolina Peacemaker, a newspaper geared toward the black community.

"But these black people are college graduates, people who hold professional degrees," she said. Many of the city's blue collar African-Americans still live on the city's east side, where they've been concentrated for generations.

"It's really a class issue in a lot of ways," she said. Schlosser, the civil rights reporter, said Greensboro "is a far more residentially integrated community than it was 25 or 30 years ago." However, "people may live in the same block or same neighborhood, but they don't socialize together very much," he said.

Historic reconciliation, politics or business might be the path to easing the tension in this city, but some are trying a different route: Sunday mornings. Martin Luther King Jr. referred to Sunday morning church services as "the most segregated hour in Christian America."

Greensboro pastors Adrian Starks, who is black, and David Longobardo, who is white, fought to break down those walls in 2009 when they merged their predominately black and white congregations.

Their new church, World Vision International Christian Center, has dropped from 50% white in 2009 to 30% white today, Starks said. He said white worshippers don't always easily accept black ministers. "One of the white members said, 'I didn't sign up for a black pastor, and I never will,' " Starks recalls. "I was disappointed, but I expected this not to be easy."

There's no denying that race relations in Greensboro have gotten better than they were decades ago, Starks said. But as the city continues to change, there's more work to be done.

"I certainly don't believe that we've arrived," he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment